“Welcome to Brunei,” says almost everyone we meet in this friendliest of countries.

“How long you stay?”

“One week.”

“Oh no. Too long, too long. There is not so much here for you.”

I felt at the start that was a weird thing to say. By the end I was happy to tell them they are wrong. Of course, anybody could tick off the main city centre tourist attractions, such as they are, in a couple of days. However, I am delighted we stayed longer (pairing this week with another diving Barracuda Point at Sipadan in Malaysia, also on Borneo). With 48 hours in the capital, Bandar Seri Begawan, a day driving around the western oil heartland and dipping into local Iban culture, an overnight stay to explore the best protected and most pristine rainforest on the whole of Borneo at Ulu Temburong National Park in the eastern enclave, plus a day or two diving in Brunei Bay, even before you throw in a morning on the golf course and an afternoon by the pool at the country’s premier hotel and country club, and you have a busy and rewarding itinerary. As the signs all over say, without the sucker punch, selamat datang.

I would bet that not many people have ever heard of the Sultanate of Brunei, and I would double down that even of those a substantial proportion could not find it on a map because they think it is somewhere in the Middle East. In fact, this tiny country – formally titled Brunei Darussalam, meaning Abode of Peace – comprises just 1% of Borneo in South East Asia. It is the only sovereign state located wholly on the island, the rest being Malaysian Sarawak and Sabah (26%) in the north and Indonesia Kalimantan (73%) in the south. Of the 23 million people on Borneo, less than half a million are in Brunei.

Borneo was part of mainland Asia before sea levels rose at the end of the ice-age, flooding the surrounding plains and leaving this landmass the largest island on the continent and the third biggest in the world. Bounded by the South China Sea to the north and west, the Celebes Sea to the east, and the Java Sea to the south, the equator runs more or less through the middle of it. Its rainforest is estimated to be 140m years old and is home to many endemic species of plants and animals, most famously the endangered orangutang (which does not live in Brunei).

Cave paintings have been dated as far back as 40,000 years, and Borneo was a thriving centre of trade between China and India from the sixth century. Islam was brought by merchants in the tenth century, quickly displacing indigenous Buddhism, and four hundred years later the island split when the northern Sultanate of Brunei was formed and declared independence from the Sultanate of Sulu, which controlled the rest.

Brunei began a Golden Age under Bolkiah, who ruled as its fifth Sultan from 1485 to 1524 and established a dynasty that has been unbroken for 600 years. Its thalassocratic power expanded its sovereignty across most of the island to include what is today Sarawak, Sabah and large swathes of Kalimantan, even extending as far as Manila and the Sulu archipelago in the south-west Philippines.

Borneo was discovered by Europeans in the sixteenth century from when in turn Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch and Germans all opened trade links but struggled to conquer it due to pirates on the coast and head-hunters and cannibals in the interior. However, in the nineteenth century, following numerous civil wars and the emergence of the East India Company, Brunei’s empire finally began to decline and the Sultanate was forced to cede large chunks of land in the north to various British adventurers before much of it became a British Protectorate in 1888; most of southern Borneo succumbed to the Dutch three years later.

Borneo’s tragic history as a regional battlefield for global conflicts reached its zenith during World War Two, when much of the island was occupied by Japanese forces. They invaded on 16 December 1941, eight days after Pearl Harbour, and for four years brutalised indigenous and Chinese residents and built camps to hold thousands of British and Australian prisoners of war. At the end of the conflict, southern Borneo was included in the new republic of Indonesia while Britain retained its colonies in the north, including Brunei.

A new constitution was adopted in 1959 that declared Brunei a self-governing state with full control of its domestic affairs, and by the early 1960s Britain proposed merging all its Borneo territories into the new federation of Malaysia. However, following a rebellion against the monarchy, the Sultan of Brunei pulled out of the North Borneo Federation, the rest of which went on to join Malaysia when it was formed in 1963.

Since way back in 1967 Brunei has been looking up to its diminutive twenty-ninth ruler, His Majesty Paduka Seri Baginda Sultan Haji Hassanal Bolkiah Mu’izzaddin Waddaulah Yang Di Pertuan, who also became prime minister when Britain finally withdrew and granted independence in 1984 (though Gurkha units remain to this day as part of his security detail). It is fair to say that he has been something of a controversial figure.

On the one hand, the reign of this absolute monarch has been characterised by administrative competence and economic development. Oil had been struck near the Seria River in 1929, and the first offshore well drilled in 1957, though it was not until the late twentieth century that production got into full swing. In the early twenty-first, the nation has been transformed by bulging oil revenues, which today make up about 90% of its GDP, into a modern industrialised economy. From 2000 to the global financial crash of 2008, GDP rose by a staggering 56%, making Brunei one of the five richest countries on the planet by GDP per capita, with free health care, free education and zero tax for all its citizens.

On the other, Sultan Hassanal has isolated Brunei from the world and straightjacketed it in a conservatism far from the modern Islam of neighbouring Malaysia or Indonesia. Since 2014, this has been the first and only country in East Asia to impose the penal code from Sharia Law onto the country’s Muslims, who comprise two-thirds of the total population. Homosexuality is illegal, with men punishable by death or whipping and women by imprisonment or caning, causing the United Nations to express “deep concern”. Such was the backlash that parts of the penal code, including amputation and death by stoning for theft and drug offences, were quietly repealed in 2019. There is no political dissent and no free media, as you will see if you flick through the Borneo Bulletin or the Brunei Times, both in English, though the internet is uncensored.

In practical terms for visitors, alcohol is not available in the country anywhere, although foreigners are allowed to bring with them up to 2 litres each for consumption in private. While there is social pressure for women to cover their heads – I did not see any burqas on the streets – it is not a legal requirement and most tourists dress as they would in any conservative environment; for men, shorts are common. Local clothing tends to be colourful.

It is very easy to get in. There is a Royal Brunei Airlines flight several days each week from Heathrow that bounces briefly in Dubai, as well as services from major cities in South East Asia and the Far East. You pick up a 90-day visa on entry.

It is also easy to get around. There are Avis and Hertz desks at arrivals in the airport, though as they have a limited fleet you would be advised to reserve in advance. Otherwise taxis are hard to hail on the street and usually need to be booked for you by a local such as your hotel or restaurant. Bruneians drive on the left.

The official language is Standard Malay, for which both the Latin and Arabic alphabets apply, though the principal spoken language is the slightly different Brunei Malay; Mandarin and English are also widely used. The Brunei dollar was introduced in 1967, since when it has been pegged at parity with the Singaporean dollar. Few foreign firms have telecoms deals so data connectivity is an issue; it is advisable to get a local SIM.

The northeast monsoon season is December to March and the southwest one is June to September, so the best time to come is April-May or October-November when the skies are blue, although there can be sudden tropical downpours.

In this friendliest of countries, Bruneians even offered to buy goods in shops for us when we had no small change. One idiosyncrasy is that they point not with their index finger but their thumb.

Bandar Seri Begawan

Universally known as BSB, the capital is set on the north bank of Brunei River, to the east of its perpendicular tributary Sungai (River) Kedayan, though of course it spills a little across both. Its centre is about the same size as Clacton-on-Sea (50,000 people), and its metropolitan area is home to more than half the country’s population, the same number as Wolverhampton (250,000).

The airport is just fifteen minutes north of the centre, where there are two decent beds from which to choose: in the local Brunei Hotel or in the one international chain represented here, the Radisson, which also has what is thought to be the finest dining option around, Riwaz for Indian cuisine.

The centre itself is of course more than small enough to walk around. It is dominated by the golden-domed Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien Mosque, named after the previous Sultan, which opened in 1958. Non-Muslims can go inside from Saturdays to Wednesdays, when jubah or black robes are available to cover arms and legs. In the artificial reflecting lagoon beside it is a replica of a sixteenth century Mahligai barge, which was used to stage colourful religious ceremonies in the 1960s and 1970s. The best view comes from looking through the giant picture frame, a 9 metre-long oblong-with-a-hole-in-it, that has been erected on the edge of the neighbouring park, Taman Mahkota Jubli Emas, amid the baobab trees.

Nearby is a small parade of shops selling fake Ray Bans and Casio digital watches, Tiang Yun Dian Chinese Temple, the largest in the country, built in the 1960s, several cool coffee shops, and Nasi Katok Mama, a hotspot fast food joint for the popular dish of fried chicken and rice smothered in sambal chilli-based sauce that is served in a paper cone.

On the streets around is a signposted Heritage Walk. This takes in the Timepiece Stone Monument (the green clock tower), the Old Lapau Lama Building (used for royal ceremonies), various government offices (including the Secretariat Building and the Department of Religious Affairs), Darussalam Palace (residence of the previous Sultan and birthplace of the current one) and the Tamu Kianggeh open-air market for fruit and veg and handicraft souvenirs (from 8am to 5.30pm every day but busiest on Friday mornings).

The Royal Regalia Museum is ostensibly a display of official presents received by Sultan Hassanal from various dignitaries, along with replicas of his crowns, thrones and carriages. In reality, it presents the official history of the leader and his country since his accession in 1967. Understandably, its focus is on the path to independence in 1984. Oddly, there is no mention at all of drinking, gambling or prostitution.

Sultan Hassanal assumed power at the age of 22 and, thanks to the flow of oil, twenty years later became the richest man in the world, a position he held until displaced by Bill Gates and the tech billionaires. After years of rumours about a louche lifestyle, his carefully crafted public persona was busted in 2011 when a former Miss USA, Shannon Marketic, filed a US federal lawsuit alleging that she had been kidnapped and used as a “sexual toy”, lifting the lid on his alleged sordid private behaviour.

The Royal Regalia Museum does, however, have a section on the 2004 launch of Vision 2035, the successful plan for national modernisation that has recently been copied across the GCC countries on the Arabian Peninsula.

North of here is Tasek Park, popular with joggers and climbers. Nearby Dewan Majlis, completed in 1968, has been the home of the door-mat parliament, the Legislative Council, situated unnecessarily close to the real source of power, the Sultan’s own Prime Minister’s Office.

West of here is Gadong district, home of the main BSB mall as well as the Food Night Market, open from 4pm to midnight every day. Gadong is where to find many homely restaurants, with some of the best examples of the main types of national cuisine popular in town, including Kimchi Restaurant for Korean, Pondok Sari Wangi for Indonesian, and Seri Damai for Pakistani. Rotis are all the rage and there are two storied outlets for them: Chop Jing Chew and Iskander Curry House.

Also here is the biggest branch of the small Aminah Arif chain that specialises in ambuyat. This is the national dish, a sticky white goo made from the pith of the sago palm that has the texture and colour – and some would say taste – of wallpaper paste; it is dunked in a spicy sauce by a special pair of chopsticks of split bamboo that remain joined at the top.

Most places seem to open around 9am and close at 10pm, but are shut at lunchtimes on Fridays. For other food options take a look at this excellent blog.

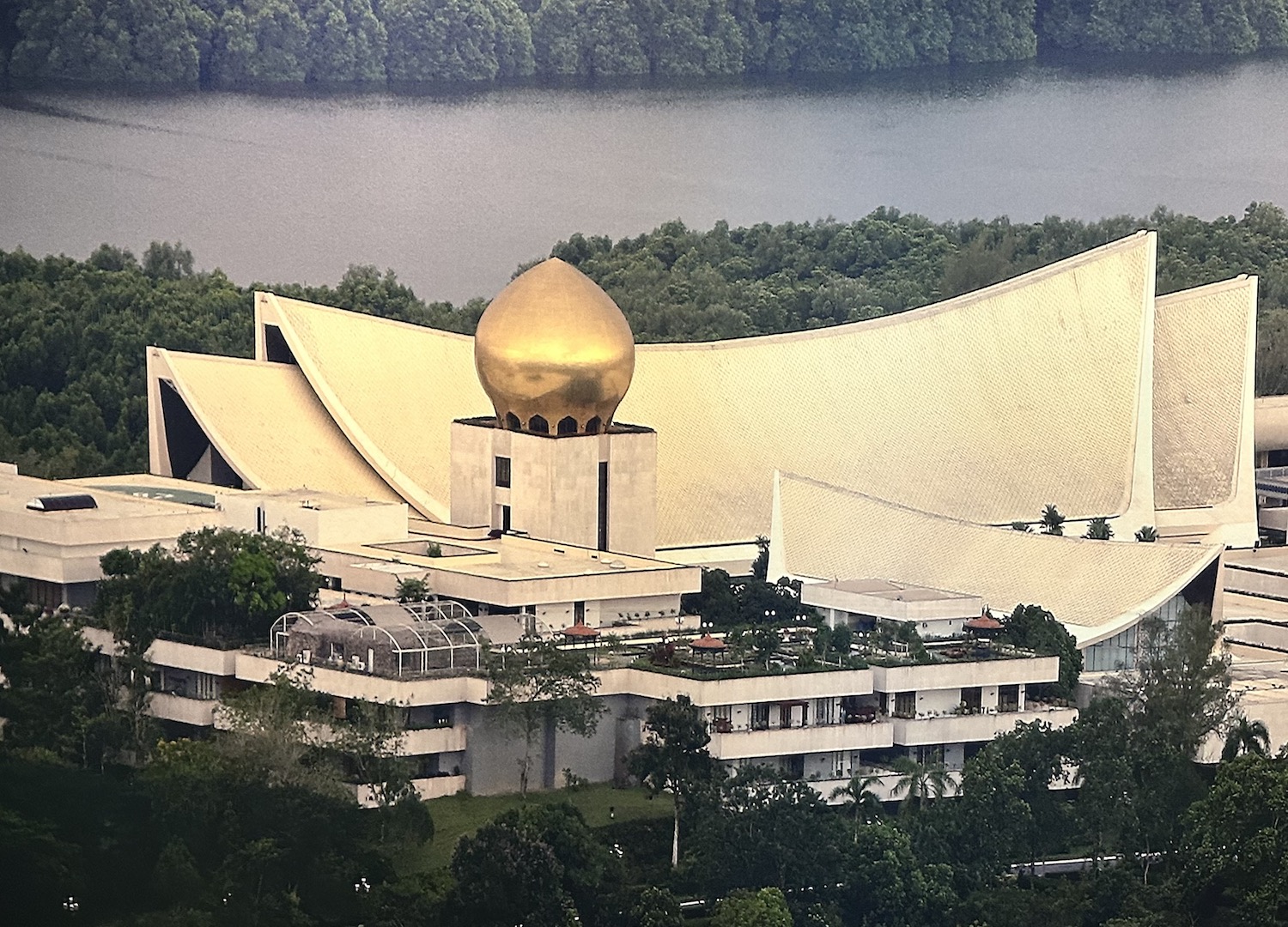

South of Gadong is Jamw’Asr Hassanil Bolkiah Mosque, the largest in the country with space for up to 5,000 worshippers. Built in 1992 to commemorate the twenty-fifth year of Sultan Hassanal’s reign, it has twenty-nine golden domes to recognise he is the twenty-ninth Sultan, as well as four minarets reaching 58m and intricate gardens. Non-Muslims can visit (all but Thursdays and Fridays) between 8 and 11.30 in the morning and 2 until 3 in the afternoon.

South again is the most famous asset of the world’s former richest man: Istana Nurul Iman Palace. With 1,788 rooms, this is the planet’s largest private residence, bigger even than the Vatican. In keeping with Islamic tradition, Sultan Hassanal has historically opened his home to the public every year over the three days of Eid Al Fitr at the end of Ramadan, when up to 50,000 people a day queued for hours to enter (men were greeted by him, women by one of his three wives) for a buffet of curry and cake. Although foreigners were welcome, this was not a tourist gimmick – after all, there weren’t any, really, even before Covid – it was more about maintaining the consent to govern from locals, who told us they looked forward to this moment eagerly.

However, the palace has not been open since Covid. We timed our trip over Eid this year in the hope that the tradition would resume but were disappointed. With the Sultan pushing 80 there is a feeling it may never happen again.

We learned that almost everything in Brunei is closed over Eid. So instead of getting inside, we had to make do with a view of the front gate from the main road, a glimpse of the golden domed roof from a boat on Sungai Damuan, a long range panorama from a hill on the other side of Brunei River that takes an hour to climb, or a photo in the Royal Regalia Museum that makes clear beneath the snazzy roof the brutalist structure looks uncannily like the Barbican in London.

A little further along Sungai Damuan a new and large palace has almost finished construction. It is as yet unnamed, but it is widely assumed it is being made ready for the next Sultan, currently Crown Prince Al Muhtadee Billah, eldest son of Sultan Hassanal. Although you cannot see much of Istana Nurul Iman Palace from the river, you do get a cracking view of this one.

Water taxis that will cruise anywhere along the rivers of BSB are found at the small jetty near Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien Mosque, by the 60th Year Monument (the Sultan’s; it is nothing to do with collective experience). It is quite something to meander through the mangroves right in the heart of this modern capital city where there are troops of big-nosed proboscis monkeys among oodles of monitor lizards and crocodiles.

Apart from the wildlife, the main spectacle on the water is made by humans: behind posts holding up power and water cables, spread across an area of 10km2, the riverbanks are lined by forty-two contiguous villages of homes balancing precariously on stilts. This is Kampong Ayer, collectively the largest water village in the world, housing as many as 20,000 people, which I refuse to refer to as the “Venice of the East©” (you see what I did there?).

These villages are known to have been here for at least a thousand years, and during Brunei’s Golden Age from the fifteenth century they were the administrative centre and the seat of government. According to the country’s first ever census, in 1911, half of the country’s population was then living in Kampong Ayer.

Today, the ancient wooden walls and corrugated iron rooves have sanitation and rubbish disposal chutes as well as instant electricity and running water. There are police stations, fire stations and medical clinics, along with primary, secondary and religious schools. There are petrol stations, restaurants, grocery stores, a community hall and a post office. And there are several mosques, including the photogenic Pengiran Muda Mahkota Al Muhtadee.

Many of the buildings are linked by wooden or concrete bridges and walkways; otherwise the only access is by boat via a series of water jetties. To get to understand Kampong Ayer, a good place to start is the Cultural & Tourism Gallery at the main entrance directly opposite the centre of BSB. For a deeper experience, there is a homestay at Kunyit 7 Lodge.

To the east of Kampong Ayer is Raja Isteri Pengiran Anak Hajah Saleha Bridge, a 750m-long icon of the city that opened in 2017. There are great views of it from Soto Pabo, a renowned restaurant, itself on stilts above the water, which specialises in soto, soupy bowls of noodles with beef or chicken garnished with chillies and herbs.

West Brunei: Muara, Tutong & Belait

The Empire Brunei & Country Club, half an hour north of BSB on the Muara coast, is the ideal base for exploring the rest of the country. You can also play on its Jack Nicolas Signature Golf Course and loaf by one of its many pools. This is an iconic and unmissable retreat: partly because it is by far the grandest resort around, the kind of place where you have to get about by summoning a golf buggy; but mostly because of its backstory.

It is rumoured that it was originally designed as a palace for Prince Jefri, younger brother to Sultan Hassanal and a pop culture fixture of the 1990s. The owner of four wives and eighteen children as well as 2,000 luxury automobiles, seventeen aircraft, the Beverley Hills and Dorchester Hotels, Asprey of London, the jeweller-to-the-Queen, and a Superyacht named Tits, had somehow acquired the reputation of a playboy, flying in Michael Jackson and Whitney Houston to perform at private parties in specially built venues near here.

Salacious details of this private life were initially made public by enthralling journalism in Fortune Magazine in 1999 that also implicated Sultan Hassanal in hedonistic excess. However, the two fell out when the Sultan charged the Prince with embezzling $40 billion during his time as the head of the Brunei Investment Agency, which manages the vast oil revenues, and so stripped him of all his assets. This notorious tale was told in a legendary expose in Vanity Fair in 2011. Hence the notion that plans for a palace were turned into the Empire, where even today staff say they are too frightened to talk about Jefri, who has not been seen in public since.

It has been reported that Jefri’s downfall was triggered by a third brother, the pious Muslim Mohamed, who was keen to stop him tarnishing Brunei’s image as a conservative country. In this context, it is noteworthy that it was only three years later that Sharia Law was imposed, after what is likely to have been an almighty power struggle in the royal court.

The legacy today of Jefri’s profligacy is visible ten minutes west of the Empire at Jerudong Park: a pristine polo club on one side of the Muara-Tutong Highway, with a tired funfair and waterpark on the other. This was all built and offered free to Bruneians, who simply never came, turning the whole thing into a white elephant.

It is 30km west from here to Tutong beach, stretching for 7km on a thin causeway between the mangroves of Sungai Tutong and the sands licked by the South China Sea. Along the public portion of it, near signs warning of crocodiles, there are rows of BBQ huts.

It is another 75km on to Seria, the centre of the oil industry. Oil was struck here first so it naturally became the headquarters of the Brunei Shell Petroleum Company, which has had the black gold flowing at full speed since the 1970s. Every single day, Brunei produces almost 200,000 barrels of oil as well as 25 million cubic metres of liquified natural gas. The Seria Energy Lab, as the oil and gas museum is now rebranded, is on the sea front not far from the Billionth Barrel Monument (that was produced in July 1991).

After doubling back onto the Telis Al Lumut Highway, it is about twenty minutes south on Jin Labi Road into Belait district to Lalak Lake National Park, a wildlife sanctuary reached on a wooden boardwalk.

Another twenty minutes down is Lobi, a small Iban settlement. Iban people, historically famed as head-hunters, traditionally live in Longhouses. Here in Lobi there are several authentic examples, the best of which is at Teraja, which sits on stilts at the very end of the road where it is halted by the Malaysian border.

Teraja is a Longhouse shared by five families, each with a huge maze of private rooms but who share a long thin communal living space that connects them all together. There are loads of big cars parked out the front and it is worth noting that these days many younger members of the families work and live during the week in BSB, leaving older members behind to farm.

It is perfectly possible to visit Teraja independently: the guide books say you first need to register your passport at the police station just down the road, though when we tried to do that the officers looked bemused; then we simply asked a resident to show us around. Or you can book on a tour, which will include a culture show involving local food (the Iban classic is pansoh, marinated chicken placed into bamboo cylinders and sealed with bamboo leaves while it is roasted over an open fire), singing and dancing. In any case, it is polite to buy a homemade woven basket.

East Brunei: Ulu Temburong National Park

To reach the eastern enclave of the country, cut off from the western districts by Brunei Bay and bits of Malaysia, it used to be possible only by speedboat from BSB or Serasa Ferry from Muara Port. Since 2020, however, there has been road access across Sultan Omar Ali Bridge, at 30km the longest in South East Asia. Coincidentally, just like at Raja Isteri Pengiran Anak Hajah Saleha Bridge near Kampong Ayer, there are great views of it from another acclaimed soto place on stilts, Soto Babu Nini.

Only about 10,000 people, less than 5% of the total population, live in the eastern district of Temburong, some of them in Iban Longhouses. This 1,288km2 area is primarily the preserve of 2,000 species of trees and 15,000 of vascular plants as well as 500 species of fish and invertebrates, 500 of birds, 180 amphibians and reptiles, 120 mammals and 40 butterflies, though to be honest it is very hard to see any of them.

Proboscis monkeys and monitor lizards are common. Celebrity wildlife apparently includes rare exploding ants, rhinoceros hornbills, Bornean crested firebacks, flying lemurs, gibbons, tarsier monkeys, longtail macaques, banded palm civets, slow loris, horned frogs, sun bears and clouded leopards. There is a public campaign to protect endangered pangolins, which are considered a threatened treasure.

Some 70% of Brunei is covered in rainforest and 40% of that is protected by law; only 1% of it is accessible by public visitors but this is the best place in Borneo to see its full glory. Bangar town is the cute little entry point and from here it is a half-hour drive south, past the Sumbiling Eco Village, to Batang Duri or one of several small lodges nearby, to register with the rangers. From there, a motorised 4-person longboat speeds for forty-five minutes under low hanging branches and vines on the shallow green-brown Sungai Temburong far into Ulu Temburong National Park, branded the Green Jewel of Brunei.

At the end of the boat ride you are confronted by more than one thousand steps that take you high up into the forest. Then there is a series of aluminium towers that hold a short aluminium Canopy Walkway 60m above the forest floor for views of what rainforests should look like when they are not logged. On the way back there is a stop-off at a waterfall where small catfish chew the dead skin from your feet in a natural pedicure.

It is not possible to explore Ulu Temburong National Park independently; it is essential to book onto a tour at least three days ahead to allow sufficient time for the guides to arrange the necessary permits. There are half a dozen operators; ours was arranged through Abode Resort & Spa, a glamping centre in the north of Temburong we used as our base. Other activities include kayaking, ziplining and hiking. The boat on the wide palm-fringed Sungai Labu to see the sunset was especially peaceful.

Brunei Bay

Brunei River and Sungai Limbang from the west as well as Aloh Besar, Sungai Duwau and Sungai Temburong from the east all empty into Brunei Bay. This is dotted with tropical paradise islands but it is also smothered in oil rigs and oil tankers. Furthermore, it is the graveyard of several shipwrecks that attract almost two hundred species of fish, and are therefore good dive sites. As much as on land, Brunei is proud of its conservation in water too – for instance becoming the first Asian country to ban shark finning – so they are properly protected.

It is true that Barracuda Point, consistently voted the best dive site on the planet, is but a hop, skip and a jump away at Sipadan Island just off Sabah. Very few places in the world can compete with that, but Brunei Bay certainly has an appeal. The main spots are listed on Scuba Diver Life and the most common ones – those flaunted on the dive store T-shirts – are what are known as the Australian Wreck, the American Wreck, the Bolkiah Wreck and the Dolphin 88 Wreck as well as Abna Reef and Pelong Rock, which are popular among macro specialists.

The misnamed Australian Wreck was in fact a Dutch steam ship, SS De Clerk, built in 1909, and it tells a tragic story. Scuttled by the Dutch Navy in 1942 in a failed attempt to prevent its use by invading Japanese forces, it was refloated and renamed Imbari Maru. Ironically, it was then struck by a Japanese mine in 1944, while it was transporting from Singapore to Manila prisoners who were being used as slave labour. They were chained to the cargo holds and so 399 of them drowned as it went down. Today, the wreck is complete, lying on its port side at an angle of 50°, though it is slowly collapsing into the sand at a depth of 33m. The teak decks and wheel house have rotted away, giving easy access to the cargo holds, which still contain various munitions along with crockery and bottles and even some human remains. It is swarmed by bait fish that attract occasional pelagics.

The prize site is the American Wreck, the USS Salute, an Admirable Class Minesweeper, which hit a Japanese mine amidships in 1945 during pre-invasion tours of Brunei Bay. It sank with the loss of nine lives and now lies in pieces at 30m. There is various weaponry, including ammunition, and it has become home to healthy colourful corals and shoals of yellowtail jacks and snappers.

There are two local dive shops, both PADI five star centres: Oceanic Quest and Poni Divers. They are based near Maura beach. The dry season is from March to October, the best visibility is during May and June, and the water is usually calm and ranges from 25°C to 30°C.

Brunei’s most important wreck – a late fifteenth century galleon discovered by divers 30 nautical miles off the coast as recently as 1997 – is the main subject of the Maritime Museum. That is in the mausoleums and museums district of Kota Batu, to the east of BSB, and it displays more than 13,500 artefacts from the wreck.