Guangdong, formerly called Canton in the West, is one of twenty-two provinces administered by the People’s Republic of China. Of them, it has the largest economy – with an annual GDP of about US$1.5 trillion, bigger than Spain – and the largest population – over 125 million, bigger than Japan. (Incidentally, it also has a hideously unbalanced gender ratio of 130 men for every 100 women, due partly to male internal economic migration and partly to the one-child policy from 1979 to 2015 that caused the loss of so many baby girls.)

Rising up out of the mist, you can sense it believes its greatest days are imminent. Therefore, it is one of the very best places to understand what is happening in the country that has for a while been forecast to become the dominant superpower of the world. If we really are all going to be living in the Chinese century, then this is what the future looks like.

There are only a handful of official tier one cities in China, and two of them are here: Guangzhou, the province’s capital, and Shenzhen, the country’s original Special Economic Zone, are both crammed with sky-high architecture and smart-city innovation. They are part of a vast metropolitan area incorporating so many manufacturing facilities that this was the epicentre of the world’s supply chains until they were disrupted by the Covid-19 pandemic that catalysed the transition from factories to tech hubs.

Greater Bay Area

Along with Hong Kong and Macau, nine Guangdong cities (Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Foshan, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Jiangmen, Huizhou and Zhaoqing) plus all the settlements in between, are set to be merged together into a single metropolitan area of 80m people. Compute that: one megalopolis with almost the population of Germany. The plan is for the Greater Bay Area, where the Pearl River opens into its huge delta around hundreds of little islands and flows into the South China Sea, to be forged into reality within a generation, under the direction of Beijing.

All of this has been built on the foundations of a unique history. Originally inhabited by a blend of tribes known as the Baiyue, this region first became part of China during the Qin Dynasty between 221 and 206 BC. Numbers were swollen over centuries by migrants from the Central Plains who together melded the identity we know today.

Guangdong is the centre of the Lingnan culture of south China, with Chaoshan and Hakka influences as well as Cantonese obvious in the language, opera, tea shops and dim sum. It is also the birthplace of Sun Yat-sen, the universally acknowledged founder of modern China. So as well as the future you can also visit the past in villages, fortresses and temples dating back thousands of years. On top of all that, you can join local holidaymakers playing in the beautiful blue-pine forests of the Nanling Mountains to the north, and even loaf with them on the beaches of the south-west coast.

Lingua Franca

Mao Zedong proclaimed that written characters in Chinese languages were too complicated for many poorly educated people to grasp. Hence, he issued edicts in 1956 and 1964 that reduced the number of pen strokes to be used in the 85,000 characters listed in Chinese dictionaries. (Incidentally, Pinyin was created in 1958 to transliterate them into the English alphabet to help foreigners learn them too; it is estimated you need at least 2,000 to get by.)

However, some opponents of Beijing resisted these edicts, which is why today there are two written Chinese languages: the “traditional” version used in Hong Kong (Cantonese-speaking) and in Taiwan (Mandarin-speaking) as part of their opposition to Chinafication; and the “simplified” official version on the mainland, where two generations from now traditional Chinese will be more or less extinct, preserved only for academic interest much as Latin is in Europe.

These days, Beijing also discourages all local spoken languages, including Cantonese in Guangdong. Schools now solely teach Mandarin, so soon only pensioners here will know their historic Cantonese tongue.

Until China began to open up over the past thirty years, much of the West’s understanding of Chinese culture was based on Guangdong: most foreign Chinatowns were built by Cantonese migrants speaking Cantonese, and most Chinese restaurants abroad served Cantonese dishes, because this was the region most engaged with the rest of the world. After all, it has more than 4,000 kilometres of coastline, it was at the start of the Silk Road and it benefited from the Canton System by which the Qing Dynasty sought to limit outside influence through a decree anointing Guangzhou the only port in the country exposed to foreign commerce.

I have been to Guangdong many times, not least when I lived in Hong Kong, and I have divided this review between the three main bases of Guangzhou, Shenzhen and Zhuhai, using them to jump around their localities.

All year round the air can be muggy, heavy with humidity and thick with MSG too, but in general the winters are short, mild and dry, and summers are long, hot and steamy. It can be so changeable it is hard to tell whether women are carrying parasols or umbrellas. At any time you will find local men in tracksuit bottoms with their T-shirts rolled up to their armpits, exposing their “Beijing bellies” wobbling beneath.

Essential knowledge for travelling independently in China

I am aware that many independent travellers are daunted at the prospect of exploring anywhere in China beyond the obvious. It is true it is not without its frustrations: for example, there are different rules for foreigners making various bookings, such as trains, that are cumbersome and bureaucratic in an otherwise digitally smooth country, and it can be tricky in rural areas where signage is often only in Chinese and few people speak English. Therefore, I have tried wherever possible to include lots of tips throughout to show that even the remotest parts rarely visited by foreigners are quite accessible with the necessary planning and effort.

I find arriving in China is always instantly intimidating, facing oodles of armed guards and barricaded immigration officers taking my snapshot and my fingerprints under constant CCTV surveillance. Even in spring 2024, many of these authority figures are still wearing masks, and we were even shepherded for a quick throat swap at the airport like it was 2020 all over again. Yet as long as you have your visa it is fine.

Visas need to be sorted in advance – I keep renewing my two-year repeat entry – and they are easily arranged from the Chinese Embassy in your home capital. It takes just three or four days with a sourcing agent like DJB.

Although you can get yuan renminbi (meaning the “people’s currency) from ATMs in the big cities, China is now pretty much a cashless society, and credit cards are taken only in the major hotels. Even the wheelbarrow hawkers of fruit and coconuts have a lanyard with their own QR code to scan with Alipay and WeChat apps. It is essential to download them and upload links to your credit cards before you travel. Of course, it means the authorities know your every move, but it is the only way to get by.

Mobile coverage is good everywhere and there is no need to get a local SIM card unless you want to bypass restrictions on foreigners booking some local services such as hiring dockless bicycles.

Only people with a Chinese driving licence are able to hire a car, so for almost all foreigners travel over long distances is by train, and short distances and rural areas is in cabs.

Cabs can be hailed on the street though it is more common to use Didi, whose rides are booked through the services feature on Alipay and We Chat. They invariably arrive within five minutes, even in remote areas, and a half-hour journey across town typically costs no more than €5.

Tickets for the super sleek brand-new high-speed surprisingly inexpensive trains are also booked through Alipay and WeChat. They have three classes: Second is pretty comfy and has cool reversable seats that swing round when the direction changes; First has just a bit wider seats; and Business is like a first class plane, with at-seat dining and reclinable flatbeds. Stations are usually massive and way out of town, so it can take up to an hour to reach them from a city centre and then another good while to walk through them to the platform. From Guangzhou it is precisely 29 minutes to Shenzhen, just 49 to Zhuhai, and only 41 to Hong Kong; there are also slower-but-still-quick trains to smaller cities in the province, and metros in the big cities.

Google Maps do not work well here but Apple Maps have much more accurate coverage. Luckily, Google Translate does work and you are likely to spend a fair bit of time shouting messages into your phone, echoed back by various taxi drivers, restaurant waiters, shop assistants and what-not.

People think of China as rigid and inflexible and it is true that this is not the ideal place for last minute changes of plan. However, you can usually find a hotel receptionist with a can-do spirit, enough English and a keenness to help make last minute hotel, travel or activity changes. And to Westerners it is still inexpensive so if in doubt throw money at it. Nǐ hǎo.

Guangzhou & the North

Guangzhou is spread across the banks and islands of the Pearl River Delta, 120km north-west of Hong Kong and 150km north of Macau, pretty much in the middle of Guangdong. This city of 14m people is the third biggest in China; and its metropolitan area of 25m the thirteenth largest in the world. Its Baiyun Airport is 55km north of its vast main railway station, Guangzhou South, the primary interchange for high-speed routes.

In the middle of the city on the south bank of the Pearl River is the iconic Canton Tower, which opened as the symbol of the Asian Games held here in 2010. At 604m-high, for a few weeks it held the record as the tallest tower in the world and it remains the second tallest. At night its thin and twisting pillar glows in constantly changing bright neon colours.

It is not only striking from the outside, but it is also great fun on the inside. There is a Bubble Tram that hovers over the lip of the building at 460m, a scary Sky Drop just above that, and an outdoor lookout at 488m that helps you get your bearings as well as give you vertigo.

Immediately north of the Canton Tower is Haixinsha Island, which includes Asian Games Park and a huge single-sided grandstand for the opening and closing ceremonies in 2010. Almost no foreign visitors come here – we saw fewer than twenty across our most recent two-week trip around the province – but it is swarming with mopeds, scooters and bikes, whose riders have more masks than crash helmets, and it is common to be stopped for selfies with local tour groups and ubiquitous parties of blue-and-white uniformed schoolchildren.

This is a buzzy place at night because of the views of the Canton Tower on one side and the Downtown silhouette on the other, both seen through dancing fountains. It is also the best place to catch a Pearl River Night Cruise. Lurid Star Cruise ferries leave for an hour all through the evening from 7pm – the élite seats are on the open top deck – and tickets are bought from the stalls by the jetties.

Opposite Haixinsha Island on the north bank of the River is Zhujiang central business district, with its skyline of skyscrapers, including the CTF Finance Centre, at 530m the third tallest building in China and eighth in the world. In fact, Guangzhou has eleven buildings defined as super-tall, over 300m, the fourth most in the world; it also has 191 over 150m, the fifth most.

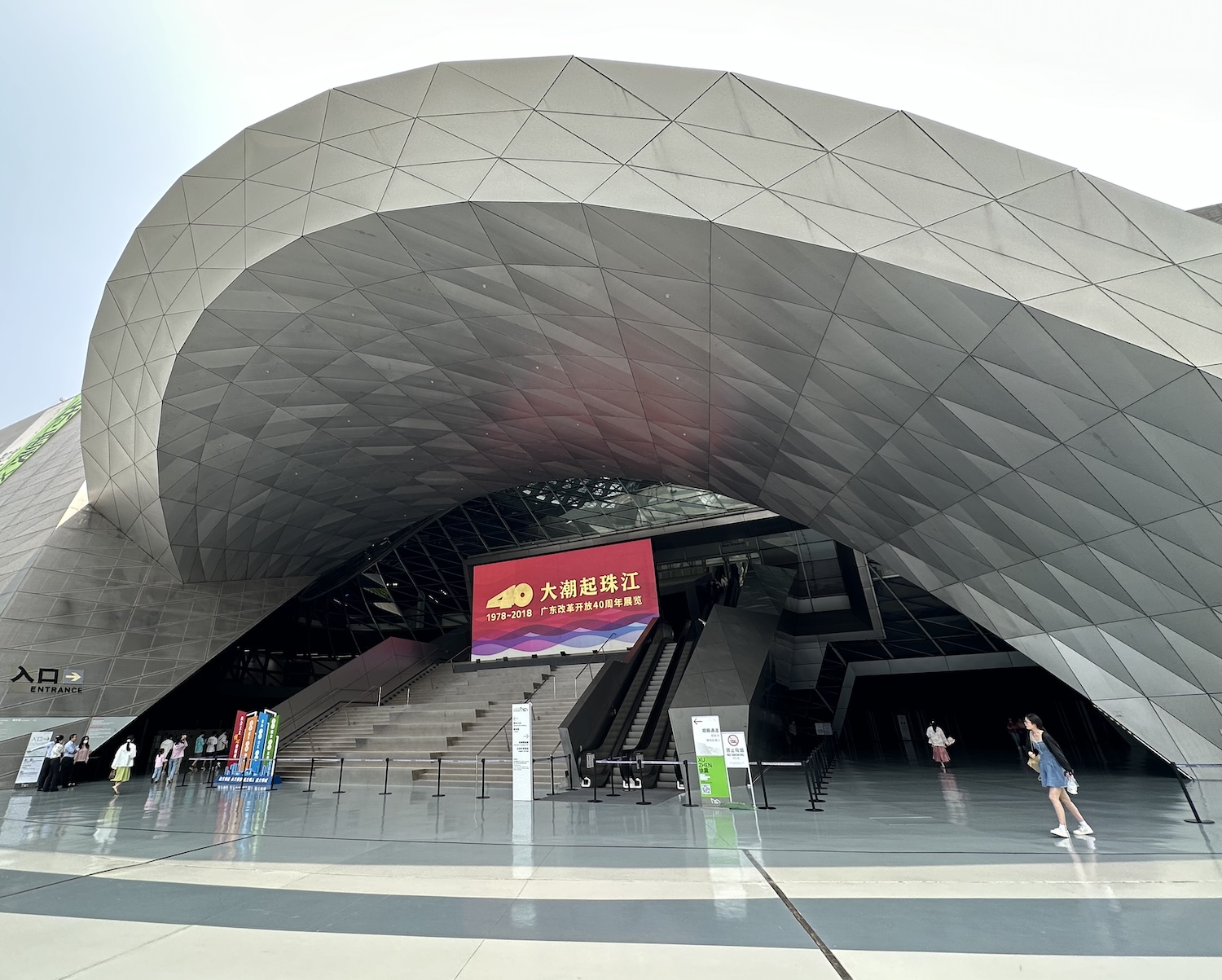

At ground level are several buildings of architectural significance, including the Museum of Guangzhou, the Guangzhou Library, and the Opera House, designed by Zaha Hadid in 2010.

There are plenty of business hotels around here but for something funky with great views, I recommend the Indigo, opened in 2023 on Haixinsha.

The next island east from Haixinsha is the much larger Pazhou, home of the twice-yearly Canton Fair, China’s biggest trade event, involving 25,000 Chinese enterprises. Held every spring and autumn since 1957, this was for decades the only way China did business with the West. It is still the main time you will see other international visitors.

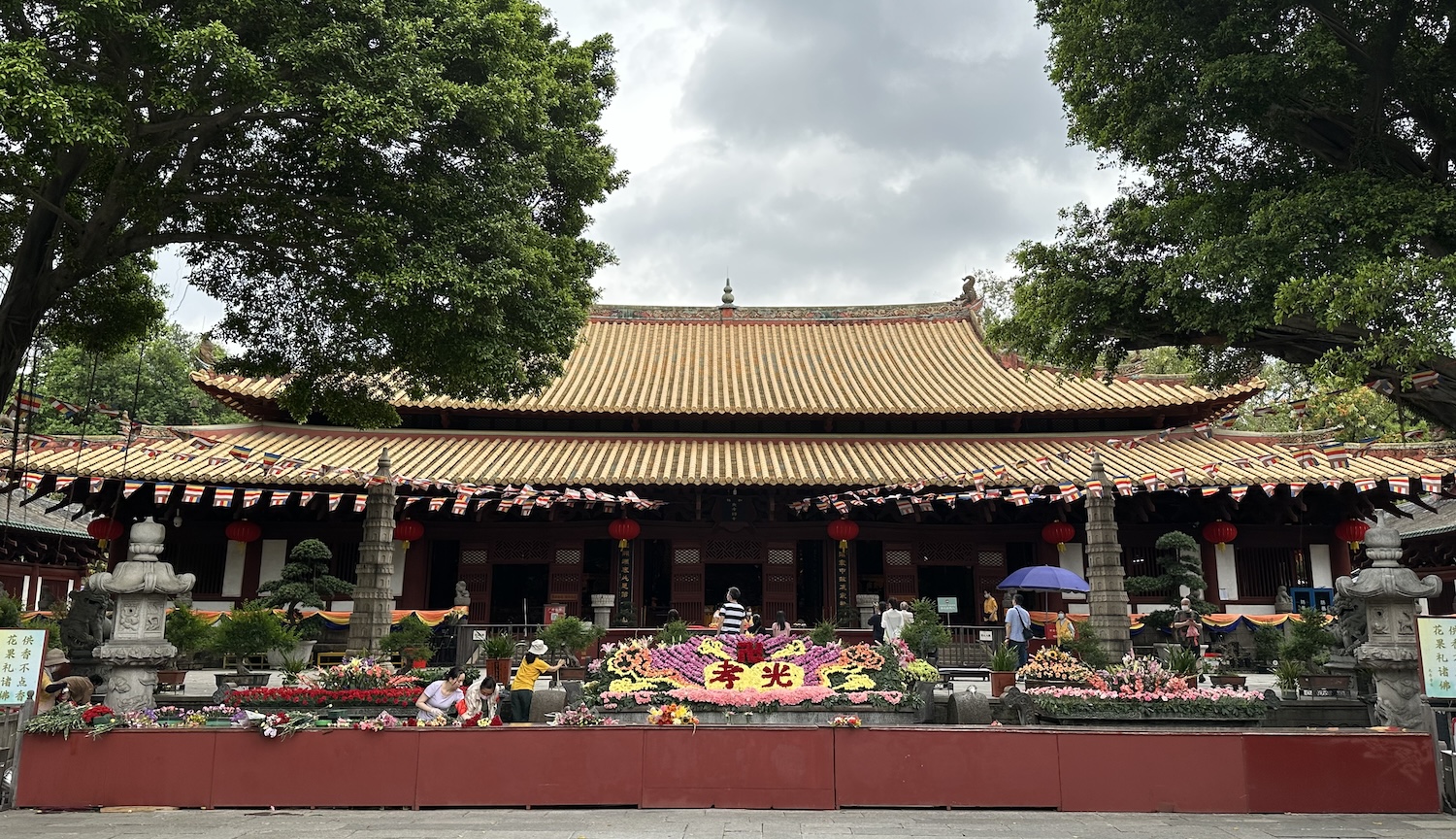

Some 10km west of Haixinsha is a cluster of ancient buildings on what is signposted as the Maritime Silk Road Cultural Heritage Trail, which is easy to walk. Liurong Temple, better known as the Temple of the Six Banyan Trees, is a Buddhist shrine built in 537 to hold relics from India. They are underneath the 58m-high elaborately decorated pagoda that dominates the front. The three huge brass Buddhas in the Mahavira Hall date from the early Qing period.

Guangxiao Temple is the oldest in the city, dating to the fourth century, though most of the remaining buildings among the giant Bonzi trees are from the nineteenth. It is highly renowned because Bodhidharma, the founder of Zen Buddhism, taught here.

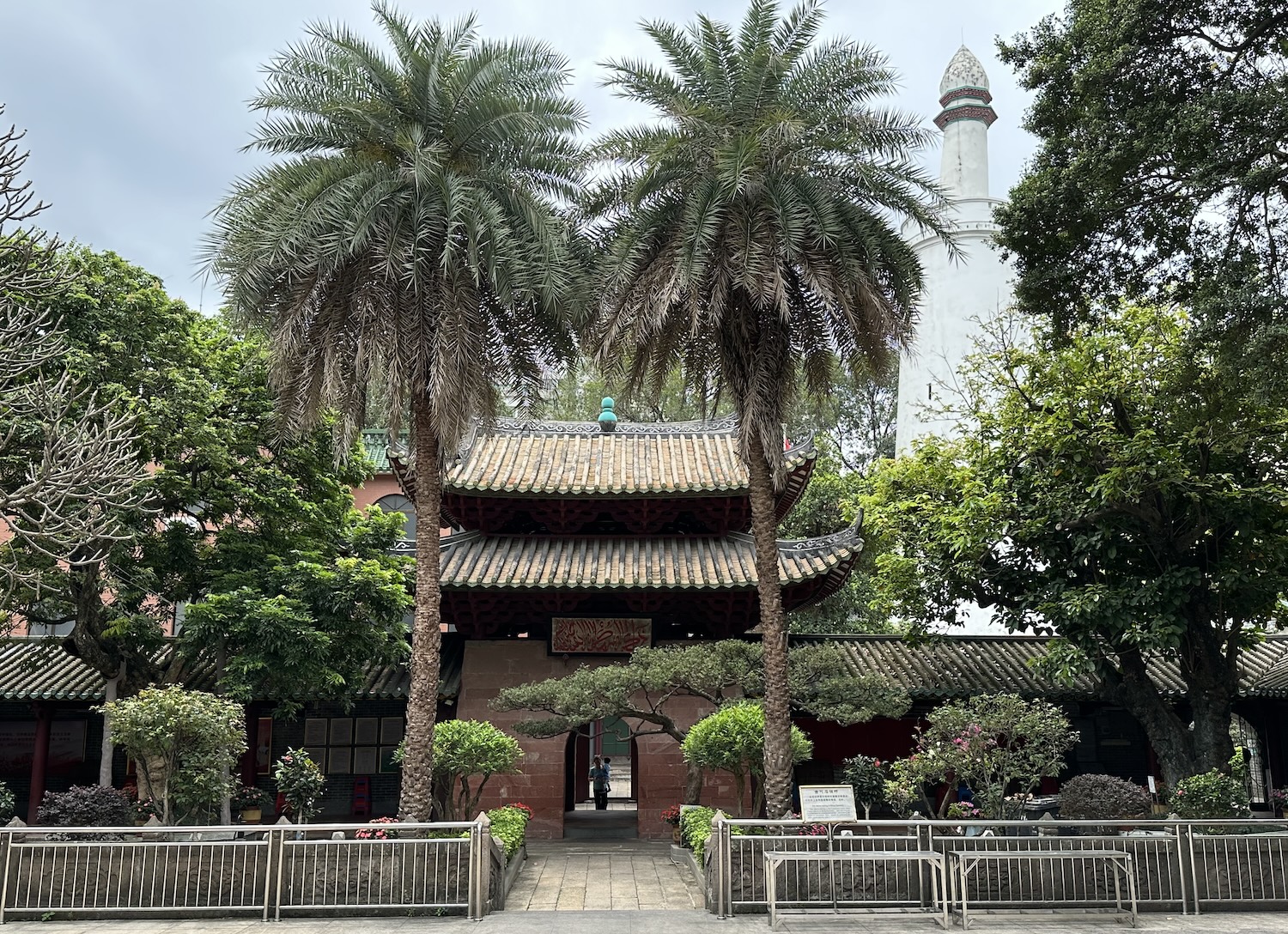

Huaisheng was the first mosque in China, built more than a thousand years ago. It is in the pagoda style; truly Islam with Chinese characteristics. Its minaret, 36m tall, is today the only Islamic tower in China. It survived because its white brick structure was visible as a navigation mark by merchant ships on the Pearl River. This batch of buildings is now smothered in bushes and trees.

Nanyue King was sent south by Emperor Qin Shi Huang of the Han Dynasty in 214 BC to quell unrest and establish a sovereign state with Guangzhou as its capital. A couple of kilometres from the archaeological site of his ruined palace is his mausoleum. Both are of greater academic interest than appeal to casual visitors.

Understandably, the most prominent building around here is the Memorial Hall devoted to the memory of Sun Yat-sen, whose statue stands at the entrance. This imposing octagonal building, opened in 1931, stands on the site of the Presidential Palace of Sun’s Constitutional Protection Movement.

Born in 1866, Sun is known by all as the “Father of the Nation” after he led the overthrow of the Last Emperor, Puyi, of the last dynasty, Qing, in the 1911 Revolution. Once the new Republic of China then slipped under the control of regional warlords, he founded rival regimes to that of Beijing in Guangzhou: first the Constitutional Protection Movement of 1917-1922, and then the Military Governments of 1921-1925. Sun died of cancer in 1925 before Chiang Kai-shek, his successor as leader of the Kuomintang, the Nationalist Party of China, launched the famous Northern Expedition from Guangzhou in 1926. This finally defeated the Beiyang government and united the country in 1928.

It is a short walk from the Memorial Hall to Yuexiu Park, a huge green space that contains a couple of intriguing sites. Zhenhai Tower was built in 1380 on a hilltop for protection against pirates. A 10m-tall granite statue of five goats dates from 1959. According to legend, immortal humans came down from heaven in response to prayers to end a lengthy famine, where they rode these goats while scattering rice, from which time Guangzhou has always enjoyed bumper harvests as the most prosperous city in the south of China.

Another 4km further west is the Chen Clan Ancestral Hall, in Liwan district, a very pretty academy-cum-shrine. There are nineteen ornate buildings built in 1894 by the residents of 72 villages where the Chens predominated. This architectural masterpiece now hosts the Guangdong Folk Art Museum.

Guangzhou has long held strategically important international trade links: for centuries it was at the start of the Silk Road, and then from 1757 through the Canton System it alone was allowed to deal with the West. Merchants sold luxury items such as tea and porcelain as well as silk in return for various goods that later included opium grown in Bengal by the British East India Company. The Daoguang Emperor’s attempt to halt this opium trade in 1839 led to the disastrous First Opium War, with the British, Portuguese and French all carving out ports in Guangdong, including Hong Kong and Macau, begetting the Chinese “century of humiliation”. It also triggered the Taiping Rebellion that nearly toppled the Qing Dynasty altogether in the bloodiest civil war the world has ever known, with up to 70m killed.

One of these concession ports, split between France and Britain in 1859, was Shamian, 9km west of Haixinsha. Shamian (“sandy surface”) was nothing more than a sandbank peninsula, but the imperial powers dug an artificial channel across the north side to create a complete island. It is now a tranquil monument to this colonial period, with quiet pedestrian avenues shaded by huge ancient trees, dotted with public art and flanked by stone mansions. It takes just fifteen minutes to walk from one end to the other down any of three or four parallel streets to absorb the atmosphere.

All day you will find lone karaoke singers, large choirs, troupes of line dancers, couples playing badminton without a net, groups of friends kicking a jianzi foot-shuttlecock, gangs of older people doing tai chi, often with swords, classes of kids sitting at easels drawing pictures of the scene, and joggers on the little running track, all while traditional music leaks from shop fronts.

There are cafes and art stores, even a Taiwan Bank, and at the east end is the Church of Our Lady Of Lourdes, built by the French in 1892. Many churches and other monuments were destroyed during the Cultural Revolution, and in recent years there has been an escalating conflict between the Chinse government and the Vatican that started as a row over who should have responsibility for the appointment of archbishops in China and has included allegations that many church buildings have been destroyed. This one, however, is picture perfect.

The ideal base to explore the old parts of west Guangzhou is the five-star White Swan Hotel, on the south-west corner of Shamian. It has spacious rooms with views, a well-equipped gym, a relaxing pool by the river, and an excellent Chinese and Western breakfast. A short walk east of the island, across the bridge onto the north bank of the river, are more classic structures, including the Post Office and the Custom House.

Another short walk, this time across the little bridge north of Shamian, is Qingping Chinese Medicine Market. This cluster of 1,200 booths selling herbal remedies as well as dried fish, fruit, flowers and pets is the biggest of its kind in south China.

Qingping runs into Shangxiqjiu Pedestrian Street, where the energy and general hubbub make this unlike Western shopping precincts. Young women stand outside the shops clapping, banging drums, and waving signs to encourage you into their stores, where a young man, likely to be standing on a table displaying goods at the entrance, will greet you with pointed directions to where you will find whatever he thinks you want to buy. It is great fun.

There are lots of eateries around here too, ranging from stalls displaying ducks with their heads still on and chickens with their feet off through to historic restaurants. Guangzhou Restaurant, dating from 1935, is probably the first choice for visitors looking for Cantonese cuisine. Other traditional places include Tao Tao Ju, the classic outlet for dim sum since 1880, and Lian Xiang Lou has been the home of lotus paste and moon cakes since 1889. There are a couple of Michelin-double-starred Cantonese places in the city too: Imperial Treasure, and Jiang By Chef Fei.

Heading west, Shangxiqjiu Pedestrian Street turns into Enning Lu, the main road through the historic Xiguan district of Old Canton. This was the commercial centre, the start of the Silk Road, where wealthy merchants built their luxury houses and established their entertainment venues. It was here that Cantonese Opera has flourished since the fourteenth century, and there are several important buildings around the cobblestone alleys that go back hundreds of years. These include the Bahe Academy, a guildhall for theatrical artists, Luanyu Tang, an actors’ union, and the Opera Art Museum, which is near a lovely waterway.

One of these neighbourhood buildings was owned by Li Haiquan, a well-known Cantonese Opera Clown of the 1940s. He turned out to be the father of Bruce Lee, and although the world’s foremost martial arts star was born in Los Angeles and grew up in Hong Kong, this property is cheekily marketed as his ancestral home.

Property Developers & Football Clubs

Before Covid-19, China sought to attract foreign football stars to rocket boost the Chinese Super League. Until that policy was abandoned and the league fell into rapid decline, two of the best teams were from Guangzhou, and they are both contemporary morality tales.

Guangzhou Evergrande FC, who have won more titles than any other Chinese team, played at the 55,000-seater Tianhe Stadium, awaiting the imminent completion of a new lotus-shaped arena holding 100,000. However, owners Evergrande, a property developer that had over-built and become caught in a debt crisis that has held the sector down ever since, collapsed in 2021. This triggered the downfall of the club, which in 2022 was relegated and evicted to the 18,000-capacity Yuexiushan Stadium.

That was the historic ground of Guangzhou FC, called Rich & Force after their property developer owners. In 2011, they changed their colours from black to blue, and despite appointing Sven-Göran Eriksson as manager, they struggled. In 2017, they turned to a Feng Shui Master to improve their luck. The wise old fox insisted the solution was to repaint the stadium gold, after which they did indeed perform much better, until they were dissolved in 2023.

For anyone interested in Cantonese culture – especially opera, martial arts, temples, lion dancing, and porcelain – a crucial day trip is to the city of Foshan, 35km south-west of Guangzhou. Local trains from Guangzhou South to Foshanxi take just twenty minutes and cars not much longer. Incidentally, Foshan is also noteworthy as the first place to identify cases of SARS in the outbreak that ended up infecting people in thirty countries between 2002 and 2004.

The Cantonese Opera Museum, which has more than 20,000 artefacts, is located in the exquisite Zhaoxiang Huanggong Temple, built in the late Qing Dynasty. This also serves as an ancestral hall, where there are Cantonese Opera performances held on the 1st and 15th of each month.

Two martial arts masers were born near here: Wong Fei Hung and Lp Men, a teacher whose most famous student was Bruce Lee. Both Wong Fei Hong and Lp Men have memorial halls inside the massive Zumiao Temple.

The Zumiao complex also holds a Confucius Temple, and hosts lion dances every day at 10am, 2.15pm and 3.30pm. Although they are of course aimed squarely at tourists, the only tourists are locals so it is a wonderful opportunity to enjoy watching Chinese people at a quintessential Chinese party.

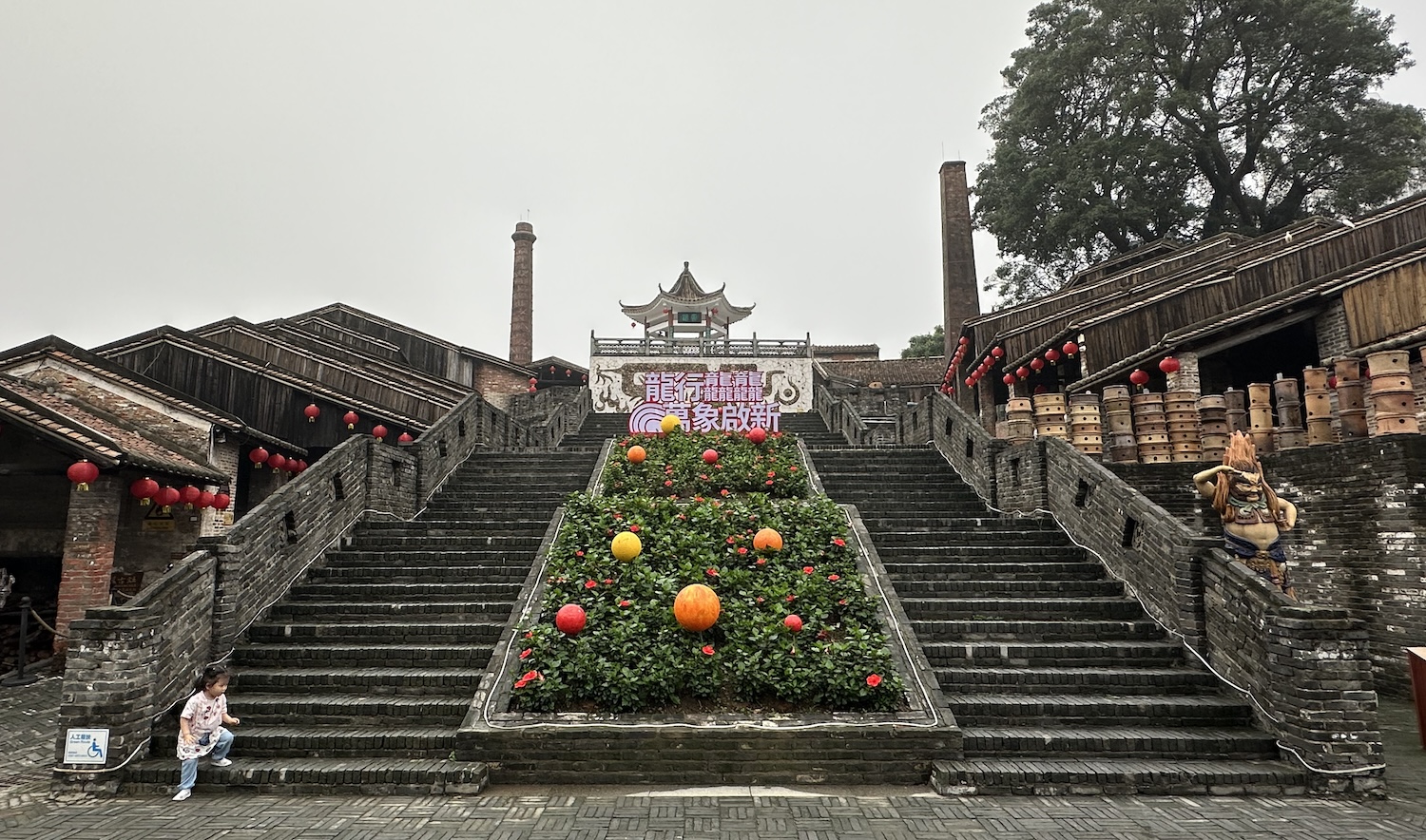

Porcelain has been made at Nanfeng since the Ming Dynasty in the sixteenth century, and its kilns tumble beautifully down a series of elegant steps, apparently in the manner of a dragon. This is now the world’s oldest kiln still in use, known for its Bonsai mudmen figurines, which are available to buy in the surrounding alleyways.

Another essential day out is to the region around Qingyuan, just above the Tropic of Cancer, 80km north of Guangzhou. Trains from Guangzhou South take less than half an hour. The city of Qingyuan itself is known for heavy industry and hot springs, but they are not the reason to come here.

Qinguan is close to the Nanling National Forest Park, a mass of blue pines beautifully smothering waterfalls and rapids all over the Nanling Mountains, the most important range in south China. The two highest peaks are Shikeng Kong (1,902m) and Shifei (1,888m), which offer decent hiking.

The main attraction is the waterfall at Gulong Canyon, which has been embroidered for tourists – though assuredly only local visitors ever come here – in a uniquely Chinese fashion.

It is a 40km drive from Qingyuan railway station into the mountains to reach Gulong Canyon, where a combination ticket will grant access to a host of ways to experience the natural beauty. These include cliff swings and rollercoasters, ski lifts and zip lines, sky bikes and what is accurately branded “a heart-stirring bridge” of wobbly rungs high in the air, a Sky Ladder and a Giant Buddha’s Hand, both designed for Instagram, glass-bottomed walkways hovering over the 100m-drop of the Wanzhangya Waterfall, and above all the 300m-long and 300m-high Yuntian Boba Glass Bridge. Breath taking in every way.

Back in Qingyuan, the wide, fast, brown River Beijiang sails along carrying mostly industrial barges. However, on each bank of the water, not far from the railway station, there are two excellent scenic hikes heading east on paved paths. On the far side, the north, which requires a twenty minute cab ride to reach the row of traditional seafood restaurants and coffee shops on stilts built into the cliff side of the Feixia Mountain Public Park, the path leads to Feilai Buddhist temple; that was sadly closed due to landslides when we were there. On the near, south side, there is a slightly shorter walk to the Temple of the Purple Bamboo Forrest. Alternatively you can take a tour on one of the many virtually empty sightseeing boats that leave from the many wharfs, though they do not actually stop at either of the temples.

Shenzhen & the East

It was nothing but a tiny fishing village and trading town until as recently as 1979 when it was allocated city status; then it was anointed in 1980 as one of China’s first four Special Economic Zones, with tax and other incentives to attract investment outside the normal constraints imposed by Beijing. Fast forward to today and Shenzhen stands as the shiny city of tomorrow. Looking down on its fading Hong Kong neighbour just over the border, this is China’s showcase to the world, no longer its industrial workshop but now its Silicon Valley, home to Huawei, DJI, ZTE and other titanic tech disruptors, with all the eco-friendly hyper-modern buildings, sculpted public spaces and waterfront ecology you might want, often done with a surprising quirky twist of fun.

Hukou System

Shenzhen is huge. Today, the registered population is about 13m but it is widely estimated that the real figure is more like 20m thanks to the massive influx of unregistered internal migrants who over the past decade have come for work outside the Hukou System.

Hukou is a system of household registration that officially records a person as a resident of a particular area, granting them the rights there to work as well as receive social benefits including education, health and pensions. Obviously, it is also an instrument for monitoring, and the breakdown of Hukou control is a potentially serious threat to government power.

In 2019 Lonely Planet awarded Shenzhen second place in its annual list of must-see cities (Copenhagen was first), and in 2024 it seems to be getting back on its feet after the disruptions of coronavirus.

Futian district is the heart of the city, 40km south-east of Bao’an Airport and 15km south of the main railway station, Shenzhenbei. This is home to the low-rise butterfly-shaped roof of the city government, and the striking architecture of the concert hall, the public library and various museum buildings.

Shenzhen is as tall as it is wide. There are five mammoth structures higher than the Empire State; in fact, 10% of all the buildings in the world over 350m are here. There are twenty over 300m, the second most in the world (after Dubai), and 410 over 150m, also the second most in the world (after Hong Kong). These glass and steel icons of modernity are serviced by wide boulevards, carrying a minimal traffic of electric vehicles, and an MTR system of immense stations that are future-proofed to serve the millions of people who are not yet here but are evidently expected to arrive soon.

The elegant 599m-high 115-storey Ping An Finance Centre, the fifth tallest in the world, dominates Futian. It has a viewing platform at 541m from where you can see blue cabs move about the streets, and green helicopter landing pads atop other skyscrapers, as well as across the bay into Hong Kong’s New Territories beyond the slim Sham Chun River that acts as the border. There is also a terrific Virtual Reality rig that sits you on a moving luge and pretends to take you on a helter-skelter ride around the outside of the building at break-neck speed.

The best view of the downtown skyline is from Lianhuashan Park at the north end of the district. In the centre of the park, on the 106m hill, is a large circular piazza with a 6m bronze statue of Deng Xiaoping, a tribute to the man who made Shenzhen.

At the foot of the PAFC are the shopping malls of Coco Park and Upperhills, a particularly chic experience that will make Western consumers look twice. Nearby, Huaqiangbei is the largest electronics market in the country, where the latest Chinese gadgets are on show, and Central Park is the favoured spot of runners, tai chiers, line dancers, karaoke singers and the like. All over are plenty of business hotels and superb restaurants, including popular local chains such as Chua Lam for dim sum, Haidilad for hot pot, and Hey Tea, along with craft breweries and baijiu bars.

Heading west from Futian, Binhai Boulevard runs beyond Mai Po Nature Reserve and all the way along the top of Shenzhen Bay. It goes past Mangrove Park and Bay Park, both of which are beautifully sculpted and have stunning boardwalks ideal for a stroll, run or cycle, as well as great views of the downtown skyline. Anglers line the route though it is noticeable there are no boats on the water, undoubtedly because of tensions with Hong Kong just over the 5.5km Suspension Bridge.

Shekou district, on the south-west peninsula, is host of the ferry terminus that services Hong Kong, Macau and Zhuhai, all about an hour away. It is also home to Sea World, an idiosyncratic leisure complex. At its centre is the Minghua, a 170m-long cruise ship once owned by Charles de Gaulle. Built in 1962, it was first moored here in 2003 when the whole area was under water, but thanks to reclamation it now stands landlocked, surrounded by fountains, restaurants and shops. It is currently under renovation, but I can testify from past trips that it has several bars as well as bedrooms, all with ornate mosaic floors, gold inlay, and stained glass ceilings. Near here are a 40m statue of Nüwa, an ancient Chinese mermaid believed to have created humanity, and a 2.5m statue of Yuan Geng, the local Communist leader devoted to market economics who definitely did create the Special Economic Zone.

Back from the bay front are two odd theme parks containing miniature replicas of well-known monuments: the Splendid China Folk Village has a hundred tourist attractions from across the country, and the Window of the World has 130 from around the globe.

The OCT (Overseas Chinese Town) Loft Creative Culture Park, on Enping Street, is heavily touted locally. A former TV manufacturing facility, now a fashionably renovated contemporary art and design space with studios, galleries, bookstores and coffee shops, it is a metonym for Shenzhen’s transition from industrial centre to info hub. It also has an acclaimed Architectural Biennale and a Jazz Festival.

At the other end of the city, east of Futian, is Luohu district, renowned for spas and fake goods, both of which have historically attracted streams of visitors from Hong Kong, though less so these days. Luohu abuts the border, where there is an MTR station just an hour from Central on Hong Kong Island. The best place to stay around here is the Shangri-La, perfectly located and full of character, plus there is a bird’s eye view over the New Territories from its 360° bar/restaurant stuck like a spaceship command-bridge on the top of the building.

Skyscrapers are not limited to Futian; there are several important giants here too. Diwang Mansion, also known as Shun Hing Square, was the tallest building in Shenzhen, China, and even the whole of Asia, when it opened in 1996; at 384m it is now the sixth highest in the city. You can get a spectacular lookout from the Meridian View Centre on the 69th floor.

The second highest in the city is KK100 (442m, 98 floors), opened in 2011. This is the tallest ever designed by a British architect (Terry Farrell) and with a height-width ratio of 9.5:1 it is one of the slimmest supertall skyscrapers on the planet. It has cracking views, especially at night, from the 96th floor.

Back on the ground there is an old part to the city in Luohu. Here, as in Hong Kong, Macao, and other major cities of Guangdong, there are tiny sub-divided apartments in walk-up tenements and tumbledown high-rises, all with anti-theft caged windows that make them look and feel like prisons. Rooted in poverty, these buildings house the staff of the spas and the fake goods trade that you are bound to encounter.

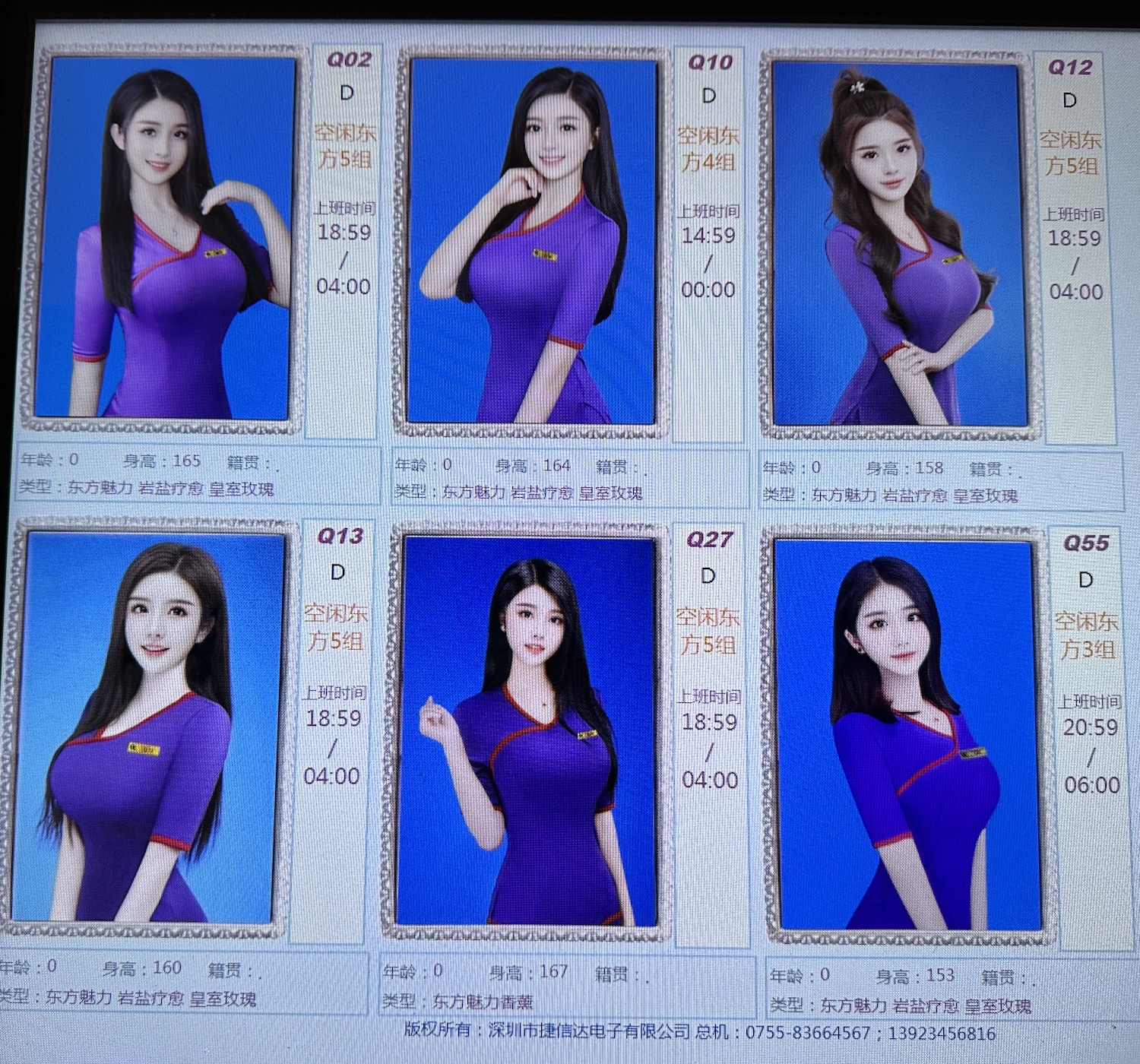

There are nail bars, massage parlours and beauty salons in almost every shopping mall and railway station in Guangdong. In Shenzhen they are rolled together under one roof in vast spas where locals come for a pampering and to rest and play. My favourite is Queen’s Spa on Chunfeng Road, less than ten minutes in a cab east of the Shangri-La; you need to show your passport to get in.

At basement level you divide by gender. On the men’s side, there are Japanese-style baths, with pools ranging from a boiling 41°C to a freezing 7°C; close at hand are saunas and steam rooms plus the cubby-hole in which you can get a highly intimate scrubbing. Once in your allocated pyjamas, you go up to the top floor where the genders mix again. Here, you can eat in the restaurant, play snooker, or relax on a bed with a private TV while teams of technicians clean your ears, scrape your feet, or tap your legs with a hammer (yes, really). Meanwhile, robots patrol the floor, fetching and carrying free fruit for the customers and instruments for the beauticians.

If you want something cosier, you can select a technician from their glamorous photograph on a computer screen and go off for a facial or a massage. It is open 24-hours a day, 7-days a week, and as there are no windows it is very easy to find you have whittled away a whole day without trying.

A three-minute walk from the Hong Kong border is Commercial City, one of the major centres in China for high-end counterfeit shopping. There are five floors of copy watches, bags and shoes – just looking-looking – reputedly made in the same factories as the originals. There are plenty of electronics, and a popular business is eye tests for spectacles made within the hour.

The originals can be found round the corner at the Mix C Mall, but here they are walking a fine line over intellectual property rights. Since the China-US trade war heated up, the most prominent brands are rarely on show; you can still get a high-class knock-off Rolex, but they are hidden under the counter. And instead of the direct copies of old, these days the pirate versions are often deliberately mis-spelled.

I have been inside these shops when they have been raided by the police, which happens a few times a week. It is a perfunctory performance really, in which the shutters come down for a while, causing a slight air of tension, before bored retailers can get back to playing on their phones outside their stores. Sellers report they believe the authorities do not want to damage their livelihoods; they also say that although trade has not yet returned to pre-Covid levels, things have been picking up over the past twelve months.

Another place to get grey goods is Dongmen Pedestrian Street. Its nightmarket begins at the McDonald’s, famous as the first McDonald’s in mainland China; it opened in 1990 and there is plaque on the floor out front. Amid the melee of karaoke singers, street food stalls, and local sports brands such as Anta, Li-Ning and 361 Degrees, there are plenty of clothes that look suspiciously similar to Levi’s, Lululemon and Nike.

Not only is Shenzhen the home of phoney watches and imitation spectacles, but also of forged artwork. Dafen Oil Painting Village, about 10km north of Commercial City, is a colony of about 10,000 artists showing their work at as many as 1,200 galleries. Although there are some originals, and you can commission anything you like, their speciality is replicas of old masters. Thousands of them are displayed in the maze of lovely cobblestoned alleys, where you can see artists at their easels or spattering around in the windows of their galleries-cum-studios. Or you can just chill at the cool cafes. It is surprisingly not at all cheesy, largely because they are not targeting tourists; most of their sales are in bulk to hotels, restaurants and interior designers, historically in Europe and the US, though since Covid that has switched more to local buyers.

To the east of Shenzhen are a number of interesting stops that make an enjoyable circuit over a couple of days. An easy cab ride of 20km, in Shatoujiao Town in Yantian district, is Chung Ying Street. Since 1898, when the New Territories were leased to Britain in the Second Convention of Peking, Shatoujiao has been divided by the border with Hong Kong, where it is called Sha Tau Kok. In fact, Chung Ying Street itself is split, with the east half in China and the west in Hong Kong; in Cantonese Chung means China and Ying means Britain. The street was originally a river, but after it dried up in the 1930s it became a Frontier Closed Area and centre of illicit trade, where clothes and jewellery were sold to mainlanders at cheaper prices from Hong Kong than they could get at home. Although this practice declined after 1978 when Chinese people were allowed to visit Hong Kong directly, it is still a popular place for purchasing cosmetics and electronics.

This was also the setting for the 2018 film No 1 Chung Ying Street, which can be found in old DVD outlets in Hong Kong. This was controversial because it used the complexities of this area to pick apart relations between Hongkongers, the British and the Chinese at a time of protest in Hong Kong.

On top of all that, there are reputed to be a number of interesting sites on the street, including the Zhong Ying Historical Museum and various Boundary Monuments. However, despite the official Chinese brochure in English encouraging visits, in reality only local residents and Chinese citizens are able to enter. So we will have to make do with this photo of the gate, which is flanked by police shelters where those allowed get their permits.

Another 35km east from Shatoujiao, or 25km from Pingshan railway station if you sensibly decide to make the rest of this loop by train, is Dapeng Fortress, a walled village of mansions and temples. Built during the Ming Dynasty in 1394 for protection from Japanese pirates, it was a key battle site in the Opium Wars. Much to my shock, this turns out not to be another site of interest for specialists, but an extremely popular tourist location usually overrun with children on school visits. There is a clearly marked route lined with tat shops and grill joints that passes a museum and the residences of various generals, though off it there are also whisky bars and stylish cafes.

The area further east, full of paddy fields and green forests, is the ancient centre of Hakka culture. There are estimated to be about 80m Hakka people, a sub-group of Han Chinese who fled persecution in the Central Plains a thousand years ago to settle in the relatively safe mountainous regions of Guangdong.

It is 320km, less than two-hours by high-speed train, from Pingshan to the railway station 20km south-west of the city of Chaozhou, which takes more than 45 minutes by bumpy road. This is a big city of 3m people, and there are several good sleeping options, making it the best base to explore eastern Guangdong: the brand new Crowne Plaza on the east bank of the Han River is the most imposing building in town, with spectacular panoramas back across to the ancient village on the west bank, where the Tide Hotel and the Yuy Hotel look good.

They are both on Paifang Jie, which aptly translates as Street of Arches, the main drag. Pedestrianised between 9am and 11pm every day, it can easily take a couple of hours to wander beneath the twenty-two traditional arches spaced along the route, dodging cyclists, scooters and rickshaws as you go. Each arch has a story to tell and the earliest dates to 1517. The arcade buildings of tea shops, food joints selling stuffed tofu and salt baked chicken, and tourist trinket stores line the way, and it is all gloriously lit at night.

Paifang Jie runs parallel to the River and between them is the Main Gate, where you can walk on the old city walls. This is at the end of Guangji Bridge, which straddles the Han with its west bank in Guangdong and east in the neighbouring province of Fujian. Originally built in the twelfth century during the Song Dynasty, though frequently rebuilt since, it is a mile long, it is the world’s first open-close bridge, and it is formally listed as one of the Four Great Ancient Bridges of China along with Zhaozhou, Luoyang and Lugou. Its current incarnation is a row of pavilions, terraces and towers with a removable central section that again all light bright at night, flooding the river with colour. It is open to pedestrians from 10am to 5.30pm.

Almost everything you will want to see in Chaozhou is off Paifang Jie in the nest of busy streets around. These include Kaiyuan Temple, Jilve Huang Ancestral Hall, Haiyang County Confucian Palace, Chaozhouzhen Hailou, and the Residence of Imperial Sun-In-Law Xi plus the large West Park. All around are Gongfu tea shops, where you can enjoy a private and intricately formal tea ceremony.

It is another 150km, about an hour on the train, north to Meizhou, an even bigger city, of 4m, that is in effect the Hakka capital, renowned for its pretty colonnaded streets in the centre and its roundhouses along the Mei River.

The railway station is 15km west of the city, and the two main sites are to the north: the Hakka Museum, and the Thousand Buddha Temple, which has exactly what it says on the tin. Built in 965 during the Han Dynasty, a magnificent edifice of mustard and saffron coloured rooves works its way across broad courtyards and up countless steps to a 36m-high pagoda atop Yanhua Hill.

Just 7km west of the railway station is Nankou Village, much heralded in guide books for its ancient housing, which is claimed to resemble Crouching Dragons lodged between hillsides and paddy fields, though my imagination failed to see it. Despite that, they are certainly unique, with dozens of white buildings contained behind a unifying semi-circular wall.

Donghua Lu and Dexin Tang are on slopes while Nanhua You Lu is unusually square and flat. Villagers still live in Nanhua You Lu and they enthusiastically charge a nominal fee for entry.

Nankou is reminder that while the urban centres of Guangdong are as modern as tomorrow, the rural areas are rooted in an ancient history and culture.

Zhuhai & the West

Zhuhai virtually surrounds Macau on the north and west, often no more than a hundred metres away on the other side of the narrow channel of water. The city’s central transport interchange is right on the border, where high-speed trains from the north come into Gongbei station, ferries from Shenzhen and Hong Kong dock at Jiuzhou port, and there is a pedestrian crossing into Macau. Jinwan airport, 35km south of here, does not handle international traffic. Although it lacks the scale and big-ticket appeal – historic and modern – of Guangzhou and Shenzhen, it is fun to while away a day or two here.

Zhuhai began to emerge as a port trading with its near neighbours during the Ming Dynasty in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and it became a Treaty Port in 1876 after China’s defeat in the Opium Wars opened new harbours to foreign commerce. The place we see today has followed the same recent path as Shenzhen, designated a city in 1979 and a Special Economic Zone in 1980. It remains a manufacturing centre rather than a high-tech hub, though factories have steadily been relocating to south-east Asia for cheaper labour, spurred by the supply chain disruptions of Covid.

For visitors, the main attractions are along a 3km beach front called Lovers’ Road that begins about 10km north-east of the central transport interchange. The route sets off by the Lighthouse and the Love Post Office and twists past the Fisher Girl Sculpture that is the symbol of the city. Pearling was a successful industry in the Pearl River until the twentieth century, and she is holding a huge gem, apparently offering treasure to the people and shining light to the world.

We were lucky enough to be here on a public holiday – the Ching Ming Festival, traditionally when people sweep the graves of their ancestors – and the beaches were crammed with people enjoying themselves in a uniquely Chinese way: standing around, fully covered up against the sun, taking selfies. No wonder they say Asians don’t raisin. There are no loungers and few cafes but lots of signs warning against swimming, though the views out to the Hong Kong-Macao Bridge, the longest open sea fixed link in the world, are lovely.

Lovers’ Road is ideal to walk, but it is even more popular to cycle. Colourful dockless bicycles are common on the streets of most Chinese cities, but here it is thick with them.

At the end of Lovers’ Road is Shantou Baheli Haiji Beef Shop, popular with celebrities for hot pot. Opposite is a bridge to Yeli Island, where the dominant structure is the Opera House, shaped like a pair of gigantic seashells standing up by the sea.

Jiwan Civic Arts Centre

At the end of 2023 in respected journals there were reports, accompanied by apparent photographic evidence, of the opening of a new Jiwan Civic Arts Centre in Zhuhai, designed by acclaimed Iraqi-British architect Zaha Hadid. For example, the spread in Dezeen makes the combined science centre, cultural museum and performing arts theatre all look ready to go. However, nobody local seemed to know where it might be, there is no address online, and it is not on any map. Hopefully, it’s coming soon.

Zhuhai has a couple of cheesy theme parks: New Yuanming Palace is a replica of the Summer Palace in Beijing, and Chimelong Ocean Kingdom claims to be the biggest ocean-themed resort in the world.

The cool kids go to Beishan Village, a cultural hotspot housed in a cluster of buildings constructed during the Tongzhi Period (1862-1874) of the Qing Dynasty. It has been redeveloped into a bustling community with everything from hipster barbers to motor scooter repair shops. The star turn is YDM, housed in the Yi Di Miao Temple, where you can take herbal tea and traditional pastries in the day or cocktails during the evening.

Wanzai Seafood Street is a 500m-long row of restaurants. At the back is a line of 120 stalls selling live fish; you take them into any of the dozen restaurants at the front that together have a total of 5,000 seats. You can negotiate but you must expect to be ripped off, at least twice. First, for the price of the fish: they understand market economics better than most capitalists. Then, there is a good chance the restaurant will secretly switch your fresh catch for some old stuff they already had on the grill. As long as you come here for the fun not the food, you will just smile.

For hotels, you can either stay in town – the Intercontinental, in an iconic building facing the Hong Kong-Macao Bridge, is excellent – or on the beach – the Angsana, part of the Banyan chain, on Phoenix Bay, looks good.

Just 30km north of Zhuhai, near the city of Zhongshan, is the village of Cuiheng. This is a popular pilgrimage for Chinese holidaymakers as it was the birthplace and early home of Sun Yat-sen, better known in Mandarin as Sun Zhongshan. There are more than forty Zhongshan Parks in China and the one here is of course particularly impressive. The original building, only 8mx4m, was dismantled by the Sun family in 1913. The current larger shrine is on the same site, and next door is the Sun Museum.

A two-hour drive west of Zhuhai is Kaiping, an essential destination because of its impressive diaolou. Diaolou are watchtowers built in the late Ming Dynasty by locals for protection against bandits. They are multi-storey pillars incorporating both residential and military areas in mixed Chinese and Western architectural styles. There was once more than 3,000, and almost two-thirds remain (1,833 in fact), and although you will see them by the sides of the roads all over the region, there are four main sites no more than twenty minutes apart. We booked a driver for the day at the hotel concierge in Zhuhai, and at the first spot we bought a ticket to all four. You have to use it up within two days, but you should be able to get round them all easily enough on a day trip.

A good place to start is the most northerly, at Zili village or cun, an abandoned cluster of fifteen diaolou spread around several lovely little lakes. The standout is Mingshi Lou, which you can climb up to see what life was like inside and to get the views from the top.

Just 4km south down the X555 road is Tangkou Liyuan Park, in which is Li Garden. Half the population of this area lives abroad, and this charming greenery around several impressive diaolou has been paid for by overseas residents.

Only 10km south down the G325 is Majianglong cun, a small and rarely visited site as it has only one tower and that is largely hidden by trees. From here it is another 15km south-west along the S275 to reach Jinjiangi cun, a buzzy walled village. There are only three diaolou here, but they include the most colourful. They are at the back so get to them you have to walk through immaculate narrow paths with high housing on all sides.

Not far from Zili is Chikan resort or zen, a large town of authentic ancient buildings around a network of canals that is often used as a film set. It has been rather Disneyfied – with Chinese characteristics, of course – so we did not stay more than an hour. Apart from the prettiness, it is amusing being the only laowai among the Chinese at play.

Finally, if all that burns you out, you could head for what are said to be the best beaches of south China. They are around Yangjiang, 120km away, a solid two-hour drive.